Analysis :

i. Classification of Goods or Services:

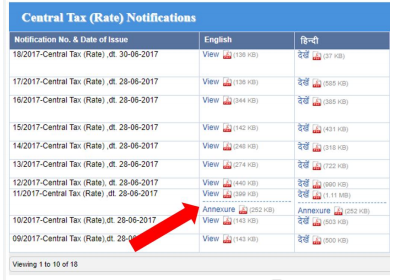

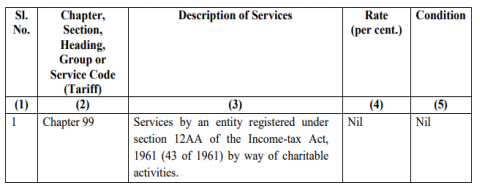

In order to apply a particular rate of tax, one needs to determine the classification of the supply as to whether the supply constitutes a supply of goods or services or both. Once the same is determined in terms of Section 7 and 8, a further classification in terms of HSN of goods and services has to be made so as to arrive at the rate of tax applicable to the supply. At the outset, it is important to note that HSN for goods are contained in Chapters from 1 to 98 and HSN for Services are contained as Chapter 99 Notified as the ‘Scheme of Classification of Services’ provided as an Annexure to the Notification issued for rate of tax (CGST) applicable to services (i.e., Annexure to Notification No. 11/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017).

The Classification of Goods is older and is based on knowledge gathered from precedents on HSN classification, as an adaptation from that formulated by the World customs Organisation. The suggested steps for determination of proper classification of goods are as under:

1. The classification of each supply has to be made separately for every individual supply, regardless of the form of supply (such as sale / transfer / disposal including by-products, scraps etc.)

2. Identify the description and nature of the goods being supplied. One must confirm that the product is also more specifically covered in the Customs Tariff. The Section Notes and Chapter Notes specified in the Customs Tariff would squarely apply to the Tariff Schedules under the GST Law, and ought to be read as an integral part of the Tariff for the purpose of classification.

3. If there is any ambiguity, first reference shall be made to the ‘Rules of Interpretation’ of the First Schedule to the Customs Tariff Act 1975.

(a) As per the Rules, first step to be applied is to find the trade understanding of the terms used in the Schedule, if the meaning or description of goods is not clear.

(b) If the trade understanding is not available, the next step is to refer to the technical or scientific meaning of the term. If the tariff headings have technical or scientific meanings, then that has to be ascertained first before the test of trade understanding.

(c) If none of the above are available reference may be had to the dictionary meaning or ISI specifications. Evidence may be gathered on end use or predominant use.

4. In case of the unfinished or incomplete goods, if the unfinished goods bear the essential characteristics of the finished goods, its classification shall be the same as that of the finished goods.

5. If the classification is not ascertained as per above point, one has to look for the nature of goods which is more specific.

6. If the classification is still not determinable, one has to look for the ingredient which gives the goods its essential characteristics.

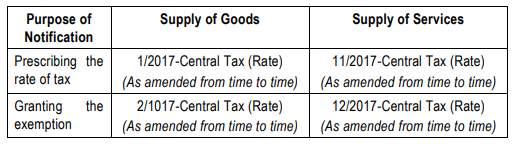

ii. Rate of tax for goods or services

iii. Requirement of Classification

It may seem like classification may not be so cumbersome, and experience, logic and common sense are sufficient tools to identify the classification, and to interpret the tariff notifications. However, a quick look at some examples would drive home the need to pay close attention to the principles of classification. Let us consider the following examples:

(1) a ‘watch made of gold’ – an article of gold or a watch, albeit an expensive one?

(2) a confectionary product ‘hajmola’ – an ayurvedic medicaments or remains confectionary sweets?

(3) serving of ‘brandy with warm water’ – classified based on its curative effect on common cold, or dismissed as alcoholic liquor for human consumption?

(4) surgical gloves – latex products or accessories to healthcare services?

(5) mirror cut-to-size for automobiles – article of glass or accessories to motor vehicles fitted as rear-view mirror?

As can be seen from the few instances mentioned above, classification is not one that is free from doubt. When coupled with differential rates of tax, the scope for misclassification would be reinforced with motivation to either reduce the tax incidence / or to pay a higher tax to circumvent any possible interest and penalty . Both these motivations can work on either sides – industry as well as tax administration. Classification cannot, therefore, be left to the whims and fancies of each person, and reference must be had to the guidance provided in the law itself.

iv. Approach to Classification

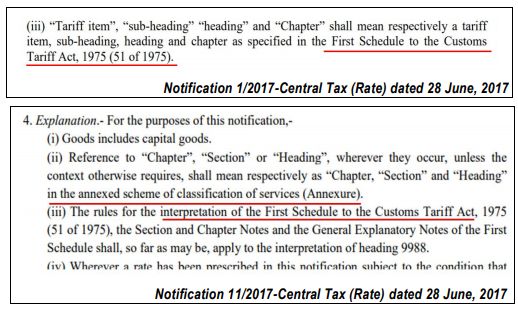

The notifications prescribing the rate of tax in respect of goods as well as services contain explanations as to how the classification must be undertaken. Extracts of some of those explanations are provided below for ease of reference:

As can be seen from the above, the notification prescribing the rate of tax itself specifies the approach that is to be followed for purposes of classification, namely:

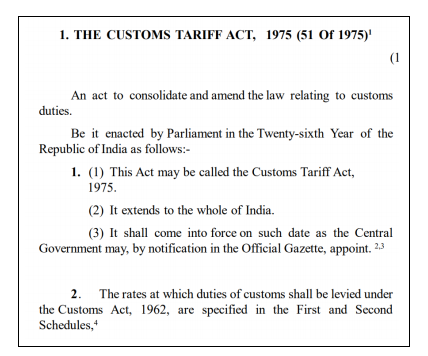

(a) in respect of goods, the notification requires reference to be had to the First Schedule to Customs Tariff Act 1975: A quick look at these helps is to recognize the approach that needs to be followed for classification.

The above table is an adaptation of the Harmonized System of Nomenclature (HSN) established for aiding in uniformity in Customs classification in international trade between member countries of World Customs Organization. It was drafted under the aegis of Customs Cooperation Council Nomenclature, Brussels. It was adopted for Customs purposes by India in 1975 and readapted (with some changes) for Central Excise in 1985 and now for purposes of GST in 2017. Please bear in mind that reference to the original HSN would be of much help in understanding the scope of any entry to understand the full extent of meaning implied in any entry found while reading Customs Tariff Act. Refer www.wcoomd.org where the HSN is available for purchase or subscription from World Customs Organization.

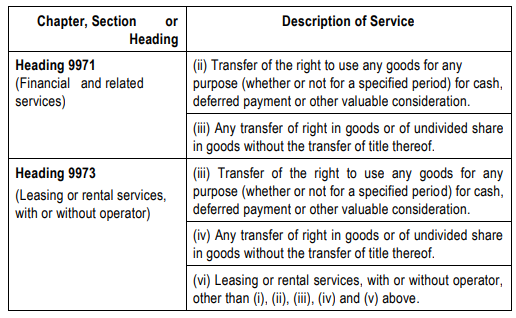

(b) in respect of services, the notification requires reference to be had to the Annexure which contains the Scheme of Classification: The Annexure is appended to the CGST rate notification and contains entries under Chapter 99 (although there is no such chapter for services in the HSN prescribed under the Customs Law):

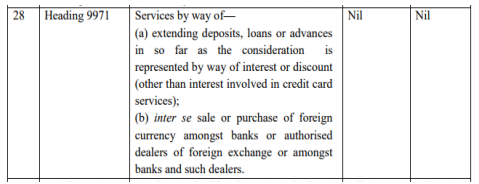

v. In this regard, it may also be noted that the tariff entries in case of certain services, make reference to the rate of tax applicable to the relevant goods. In the following cases of supply of services, the rate of tax applicable as on a supply of like goods involving transfer of title in goods, would be applicable on the supply of services:

The only exception to the above table is leasing of motor vehicle which was purchased by the lesser prior to July 1, 2017, leased before the GST appointed date (i.e., 01.07.2017 and no credit of central excise, VAT or any other taxes on such motor vehicle had been availed by him. If all these conditions are fulfilled, then the lessor is liable to pay GST only on 65% of the GST applicable on such motor vehicle. – Refer notification No.37/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 13.10.2017.

vi. Customs Tariff Act – Rules of Interpretation:

The rules of interpretation are contained in the Customs Tariff Act provides guidance regarding the approach to be followed for reading and interpreting tariff entries. These rules are merely summarized and listed below for convenience, whereas a detailed study of the rules is advised from commentaries and value added updated tariff publications. Please refer to full set of Rules of Interpretation at page 28 and 29 of the Customs Tariff Act on http://www.cbec.gov.in/resources//htdocs-cbec/customs/cst2012-13/cst-act1213.pdf

Rule 1: headings are for reference only and do not have statutory force for classification;

Rule 2(a): reference to an article in an entry includes that article in CKD-SKD condition;

Rule 2(b): reference to articles in an entry includes mixtures or combination;

Rule 3(a): where alternate classification available, specific description to be preferred;

Rule 3(b): rely on the material that gives essential character to the article;

Rule 3(c): apply that which appears later in the tariff as later-is-better;

Rule 4: examine the function performed that is found in other akin goods;

Rule 5: cases-packaging are to be classified with the primary article;

Rule 6: when more than one entries are available, compare only if they are at same level.

vii. Role of ‘Manufacture’ in Classification

Classification would be well understood by applying the above rules of interpret ation. Now, the process that goods are passed through can impact their classification. For example, cutting, slicing and packing pineapple in cans in sugar syrup has primary input is pineapple and the output is canned fruit with extended shelf-life. Now, the input and output are not identical but it has held in the case of Pio Food Packers that this is not a process amounting to manufacture. But, would it be possible to regard the input and the output to retain the same classification. The answer lies in knowing the scope of each entry applicable to classification. Another example, kraft paper used to make packing boxes may be sold as it is or after laminating them. It has been held in the case of Laminated Packaging that this process is manufacture even though the input and output fall within the same classification entry. GST Law has adopted, in section 2(72), the general understanding of manufacture that is very similar to that in Central Excise. The real test from this definition – is the input and output functionally interchangeable or not in the opinion of a knowledgeable end-user – and not based on the classification entry.

Change in classification entry from one to the other, that is, classification entry for input is not the same as that of the output, could only arouse suspicion about the possibility of manufacture. Please note that ‘manufacture’ is included in the definition of ‘business’ (in section 2(17)) but it is not included as a ‘form of supply’ (in section 7(1)(a) or anywhere else). Hence, the nature of the process that inputs are put through may not be manufacture but yet may appear to move the output into a different entry compared to the input. So, would change of classification entry be relevant or degree of change produced in the input due to the process carried out must be considered. With the adoption of HSN based classification from Custom Tariff Act, it is imperative to carefully consider whether one entry has been split and sub-divided into categories even if they both carry the similar rate of tax. Hence, the key aspects to consider are:

Identify the scope of an entry for classification of input or output

Study the nature of process carried out on the inputs

Examine by the ‘test’ (above) if result of the process is manufacture

Now identify the classification applicable to the output

For example, is ‘desiccating a coconut’ a process of manufacture? If yes, the desiccated coconut ought not to be considered as eligible to the same rate of tax as coconut. Drying grains may not appear to be a process of manufacture but frying them could be manufacture as the grains are no longer ‘seed grade’ although it resembles the grain.

Manufacture need not be a very elaborate process. It can be a simple process but one that brings about a distinct new product – in the opinion of a knowledgeable end-use – and not just any person with no particular familiarity with the article. Manufacture need not be an irreversible process. It can be reversible yet until reversed it is recognized as a distinct new product, again, in the opinion of those knowledgeable in it. Processes such as assembly may be manufacture in relation to some articles but not in others. So, caution is advised in generalizing these verbs – assembly, cutting, polishing, etc. – but examining the degree of change produced and the identity secured by the output in the relevant trade as to the functional inter-changeability of the output with the input. If a knowledgeable end-use would accept either input or output albeit with some reservation, then it is unlikely to be manufacture. But, if this knowledgeable end-user would refuse to accept them to be interchangeable, then the process carried out is most likely manufacture. Usage of common description of the input and output does not assure continuity of classification for the two.

viii. Role of ‘Supplier Status’ in Classification

This is best explained with an illustration – a restaurant buys aerated beverage on payment of GST at 28% +12% including cess and on resale of this beverage as part of food served as a combo with ‘composition status’ under Section 10 of CGST Act, the rate of tax on this beverage would be 5%. Therefore, it is important to note that classification can undergo a change depending upon the ‘status’ of the Supplier. Another illustration could be medicaments which are taxed at 5% would be exempt from tax when they are administered by the hospital to casualty/emergency admissions and to in-patients even if billed separately in the invoice issued to patient by the hospital.

ix. Classification for Exemptions

In GST law the exemptions are set out under section 11 of the whole of the tax payable or a part of it. In granting exemptions, it is not necessary that the exemption be made applicable to the entire entry. In other words, exemption notifications are capable of carving out a portion from an entry so as differentially alter the rate of tax applicable to goods or services within that entry. Exemptions can take any of the following forms:

Supplier may be exempt – here, regardless of the nature of outward supply, exemption apply to the supplier. Conditions specified may make such exemption be applicable to the supplier but when the supplies are made to specified recipients

Supplies may be exempt – here, the supplier is not as relevant and all supplies that are notified would enjoy the exemption. Conditions specified may help to determine the supplies that are to be allowed the exemption.

x. Role of ‘Conditions’ in Exemptions

It is well understood that conditions in exemption notifications tend to convert the exemption into an option, that is, the exempted / concessional rate of tax would apply when the conditions are fulfilled and by deviating from the conditions, the full rate of tax would apply. This principle has been tested in the context of Section 5A of the Central Excise Act. However, a quick look at the Explanation to Section 11 of the CGST Act (reproduced below) appears to indicate that unless an express option is granted in the exemption notification, the concessional or exempted rate of tax along with attendant conditions must be availed without any discretion to opt out of it.

Explanation.––For the purposes of this section, where an exemption in respect of any goods or services or both from the whole or part of the tax leviable thereon has been granted absolutely, the registered person supplying such goods or services or both shall not collect the tax, in excess of the effective rate, on such supply of goods or services or both.

While there may be alternate views that the above explanation applies only when the exemption is ‘granted absolutely’ and not in all cases, such a view may find the contradiction where one entry in an exemption notification prescribes a concessional rate of tax that applies its restriction on input tax credit, while another entry in the very same notification prescribes two rates of tax where one of them enjoins restriction on input tax credit.

And the reason for resisting the view that – exemption with the condition is an option – is when the Government felt free to specify two alternate tax consequences in respect of a given entry in one case (GTA, in above illustration), there is no justification to make an assumption about the existence of an option even when in the very same notification that government opted to notify only one tax consequence. Accordingly, it would be a reasonable construction that – exemption is a condition is not an option – and all court decisions under earlier laws to the contrary are rendered otiose in view of the explanation to section 11.

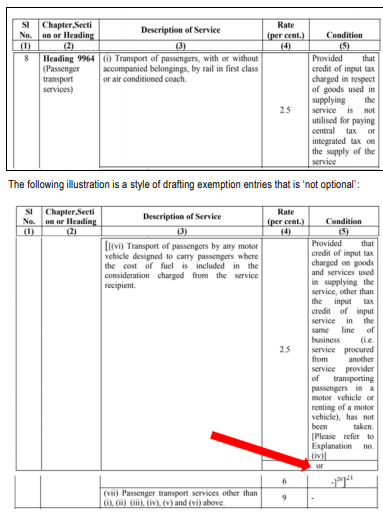

Illustration below shows a style where exemption would ‘not be option’:

xi. Conclusion

In light of the foregoing discussion, the following points of learning can be summarized:

(a) transactions involving goods are, in certain cases, required to be treated as supply of services. As such, the fundamental classification to be undertaken is the differentiation between goods and services;

(b) classification of goods and services cannot be made based on logic, experience or common sense. But, recourse to rules of interpretation in the first schedule to Customs Tariff Act is mandatory in relation to classification of goods. And reference to the scheme of classification (contained in the annexure) is inevitable in relation to classification of services. There can be no interchange in the use of the relevant classification rules between goods and services;

(c) classification in GST requires a deep appreciation of the technical understanding of words and phrases in each domain and any urge to use the common meaning of such words and phrases must be actively discouraged. In other words, even if the common meaning of certain words and phrases appears reasonable, it must be understood that government has deliberately and mindfully words that each and in the case and specific interpretation in the relevant trade;

(d) classification is not only required to determine the rate of tax applicable but also examine the availability of exemptions. There is no compulsion for an exemption notification to exempt” correctly what is the carveout from an entry a subset of transactions – supplies or suppliers – to attract a different rate of tax;

(e) exemptions are not optional as are the conditions prescribed in respect of such exemption. Violation of the condition contracts consequences and not options. ‘Absolutely exempt’ does not mean ‘wholly exempt’ and it does not require to be ‘unconditionally exempt’ to be ‘absolutely exempt’.